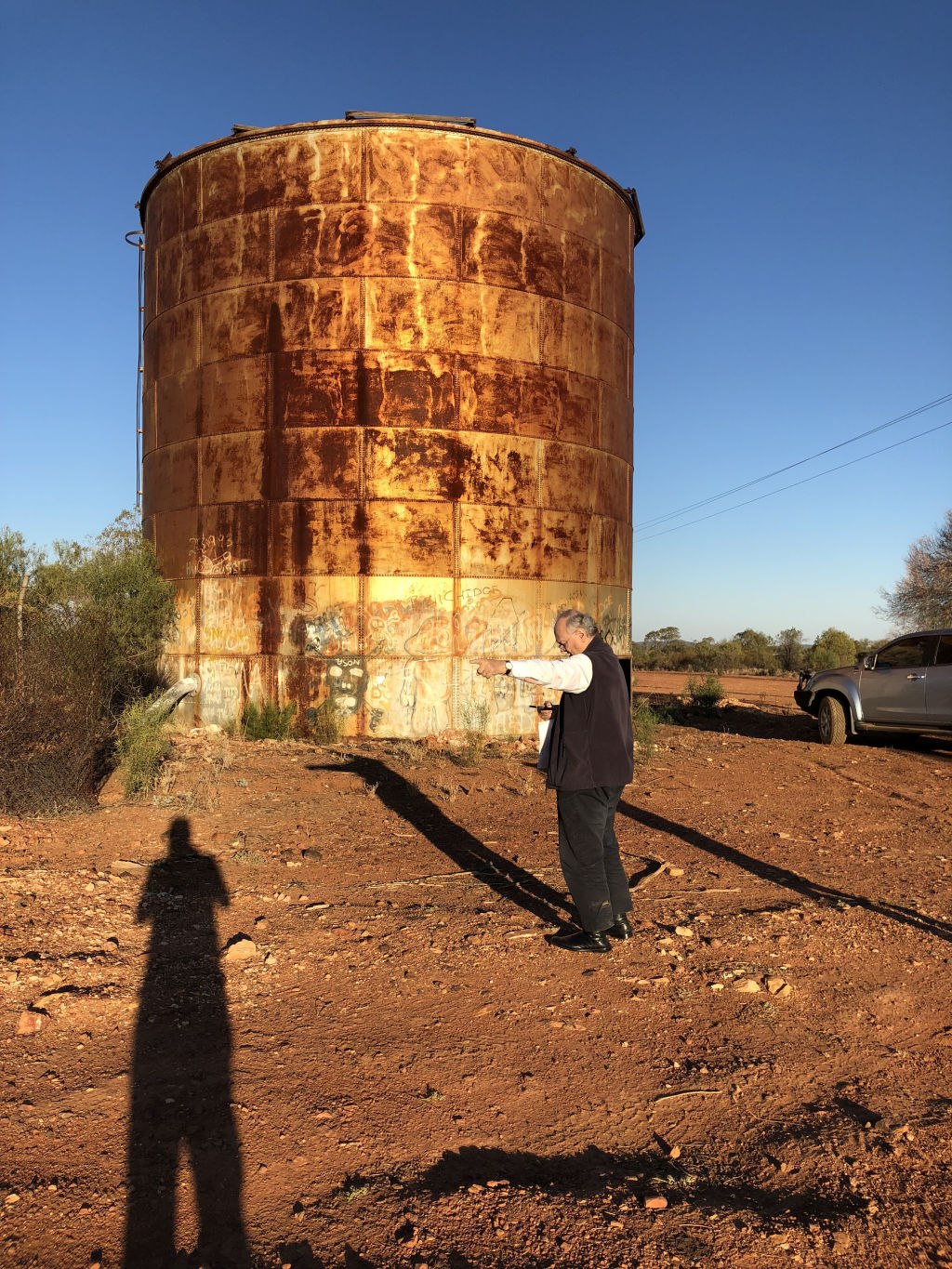

The composer, the architect and the water tank in Cobar

Australia’s latest musical collaboration is an unorthodox one. Composer Georges Lentz has commissioned Glenn Murcutt, the country’s highest-awarded architect, to design a “sound chapel” inside an abandoned 10-metre-high water tank.

The five-metre-cubed concrete chamber will be able to hold a small number of performers, but when not actively used will pipe music composed by Lentz, a Sydney Symphony Orchestra violinist, into the surrounding countryside – in Cobar, 680 kilometres west of Sydney.

It’s a long way to go to listen to music, but Lentz, who first came to Australia three decades ago from his native Luxembourg, has spent countless hours driving in outback Australia. He says the Cobar Sound Chapel – set in the grafittied 1930s steel tank in red dirt off the highway between Dubbo and Broken Hill – is the right location to play music inspired by the raw surroundings.

“I’ve been fascinated with the outback and stars of the night sky and the loneliness and vastness of the outback for years,” says Lentz.

“As you sit in the centre [of the chapel], you are surrounded by this sound. Some of this sound is incredibly soft and meditative. Some is incredibly loud and responsive to the graffiti on the walls of the tank.”

The project is also part of a growing practice of regional Australian towns, from Barcaldine in central Queensland to grain solos in Brim in Victoria, Coonalpyn in SA and Thallon in Queensland, to use architecture and art as a means of economic development – as a way to create something unique that will support local activity and draw visitors.

Cobar Shire Council is right behind it. The council purchased the tank from the NSW government and backed a successful application for an Office of Responsible Gambling $200,000 infrastructure grant to help cover construction costs.

“It’s quirky, it’s fun,” says Angela Shepherd, the council’s senior projects officer.

“You can sit down and have your lunch while listening to music rolling across the countryside. It’s an experience you can’t do anywhere else.”

Musical resource

Lentz says the work – having its final engineering drawings done ahead of an expected four-month build that should start this year – will also be a musical resource for local schools.

“We [can] work with kids on simple software for them to create their own little pieces we can workshop with them.”

The chapel itself will be open to the elements, with car audio-grade speakers on each of the four walls that can withstand the searing heat and direct rain. It will be an austere, dimly-lit room with a concrete bench in the middle, covering the sub-woofer placed on the floor.

Three visual concessions to art will be the gold-painted lip of the ceiling, shaped like an inverted cone as it narrows and opens to the sky above. A 1.8-metre-wide louvre angled over the concrete entry walls will be painted in the same shade of gold. Cut-out corners of the box will be dark blue glass, enabling visitors to see the walls of the tank within which they sit.

It’s not a typical Murcutt project. The winner of the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s equivalent of the Nobel, is better known as the person who showed Australia how to design houses that suited their natural environment, but for him it fits the idea that work has to be “responsible” (he doesn’t like the term “sustainable”.)

“Re-using the water tank, instead of taking all that steel that’s been produced and throwing it away, we’ve now got it as part of the experience of that place,” Murcutt says.

Lentz has written a composition, String Quartet[s], which at full length goes for six hours and will be played on a loop inside the chamber.

“I still like to think of the final result as a gigantic sound wall sprayed with audio grafitti,” Lentz says.

“This not inspired by Luxembourg, or the gently rolling hills of Europe.”